Ally Ring

PicoCTF - Trivial File Transfer Protocol Writeup

March 2023

I’ve been completing PicoGym challenges in the build-up to PicoCTF 2023, and recently attempted the “Trivial File Transfer Protocol” forensics challenge.

It involves packet analysis in Wireshark, but I thought I’d try and learn a new skill out of it other than “here’s where to extract files from packets in Wireshark”. As such, to complete the challenge I decided to create a script to extract the transferred files from a TFTP session to better understand how TFTP works, rather than use an existing solution.

Understanding TFTP

TFTP - or the Trivial File Transfer Protocol - is a protocol used to read files from and write files to a networked device.

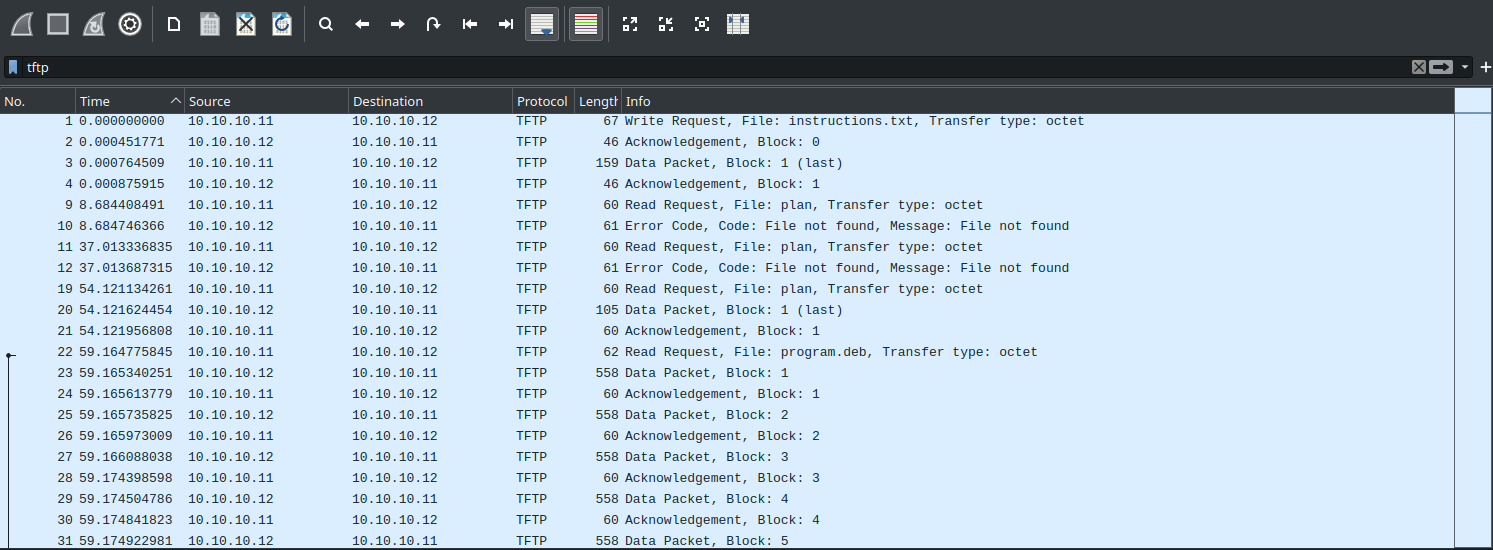

To start with, I opened the tftp.pcapng file in Wireshark to take a look at the rough structure of the data I was dealing with. I used Wireshark’s filtering function to only look for TFTP packets with the filter tftp.

By the looks of it, there are 4 main types of TFTP packets used: One to transfer data, one to acknowledge data, one to initiate a read/write, and one to indicate an error.

Next, I needed to understand the TFTP protocol, so I read through the RFC for TFTP: RFC-1350.

The protocol specification was extensive, but the key facts were that:

- TFTP can only read or write files, and doesn’t support authentication.

- TFTP uses IP and UDP packets to encapsulate data sent over the network.

- TFTP file transfers happen in order; the next block of data cannot be sent until the most recent one has been sent and acknowledged.

- All TFTP packet headers use a 2-byte opcode field that have values that vary from 1-5 inclusive, which specifies what operaton to perform, as well as additional data to expect in the header.

- TFTP data blocks are always 512 bytes long unless they are the end of a transfer.

Additionally, I searched for the default TFTP port, and found that the default listening port for a TFTP server is 69. Nice.

Reading up on documentation is always helpful, but now that I understood the protocol in better detail I decided to take a more in-depth look at the packet capture in Wireshark to identify any additional information on how a standard transfer works.

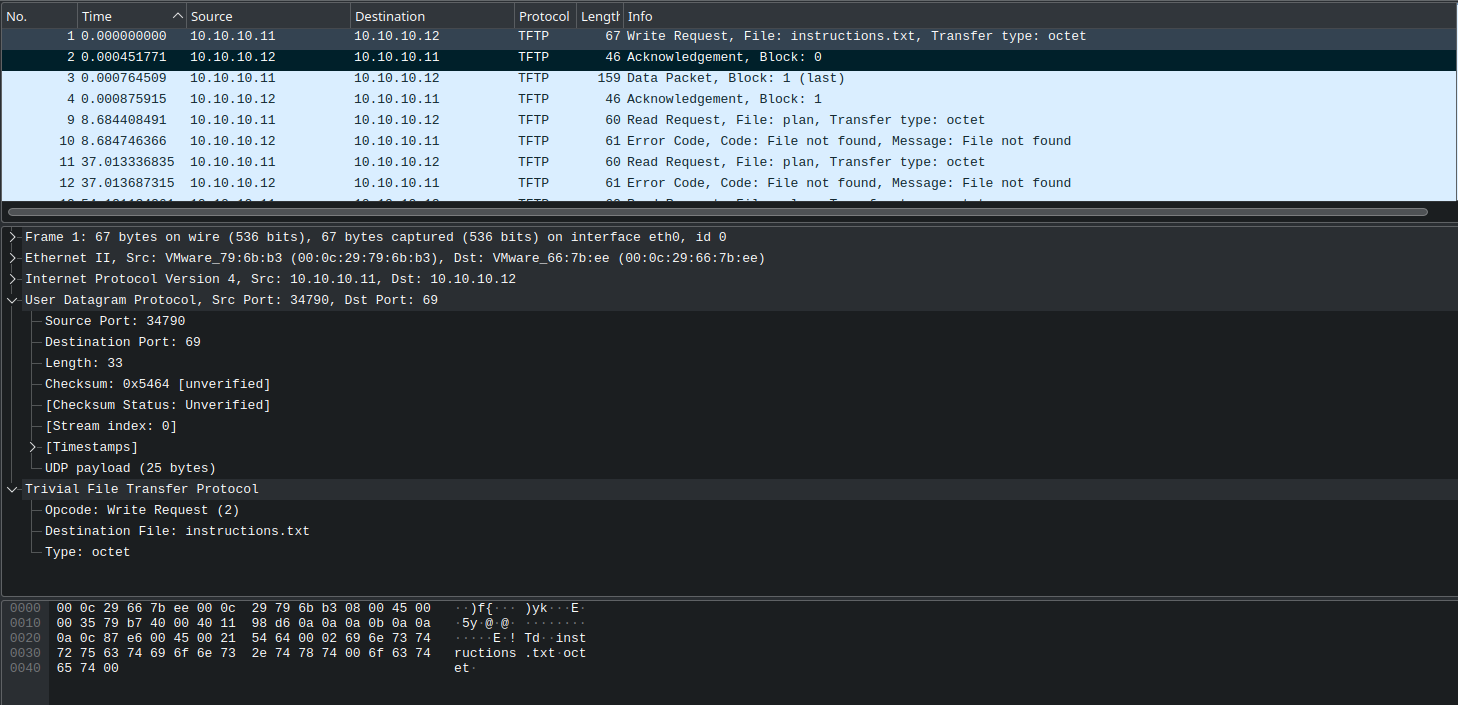

I started by looking at the initiation of a TFTP write request:

The client first sends a write request to the server on port 69 which includes the port that is open on the client for recieving data in teh UDP headers.

The server then responds to with a TFTP acknowledgement, including the port on which to continue communications over in the UDP header.

As such, our script will need to parse these ports and use them to filter out the further TFTP packets from any other unwanted packets. However, as TFTP handles both sessions and blocks of data in serial, the final script won’t need to handle tracking parallel file transfers, but it will need to handle starting a new transfer before the current one has finished as an error.

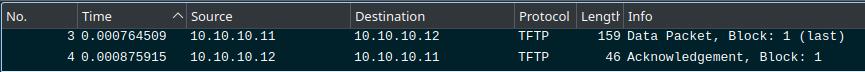

Next, I looked at the 2 packets used in the transfer process:

This showed the format of the data and acknowledgement packets that was described in the protocol specification. The specification states that:

The data field is from zero to 512 bytes long.

If it is 512 bytes long, the block is not the last block of data; if it is from zero to 511 bytes long, it signals the end of the transfer.

As such, this transfer only needed one data packet to be sent, as that packet was under 512 bytes long. In the final script, data packets should be read until one is less than 512 bytes long, then should be written to disk.

At this point, I felt that enough information had been found to start writing the parsing script.

Understanding Scapy

scapy is, in the creator’s own words:

A powerful interactive packet manipulation libary written in Python.

It’s an extremely helpful tool when developing scripts to capture, parse, modify, and send arbitrary packets of data.

In this instance, I’m going to use it to parse the given tftp.pcapng file, and carve out the files transferred over TFTPthat were captured.

In order to do this, I needed the following functionality:

- Read in the

tftp.pcapngfile as a list of packets. - De-encapsulate the packets to get to the UDP and TFTP packet headers and identify an initial TFTP connection.

- De-encapsulate the data packets from or to the server and append their raw data to a variable.

- Abandon transfers that cause unrecoverable errors.

However, scapy only includes a few packet types by default, such as IP, Ethernet, and UDP. As such, I would have to either find an existing implementation of TFTP packets in scapy, or implement them myself.

Thankfully, scapy contains a large library of existing protocol implementations, including TFTP. These additional protocols can be searched for using the explore() function in the scapy REPL.

Packets contained in scapy.layers.tftp:

Class |Name

------------|------------------

TFTP |TFTP opcode

TFTP_ACK |TFTP Ack

TFTP_DATA |TFTP Data

TFTP_ERROR |TFTP Error

TFTP_OACK |TFTP Option Ack

TFTP_Option |

TFTP_Options|

TFTP_RRQ |TFTP Read Request

TFTP_WRQ |TFTP Write Request

Writing the script

I started out by importing scapy and other relevant libraries, and set up the argument parser:

from scapy.all import *

from scapy.layers.tftp import *

import argparse

import os

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(

prog='tftp-extract',

description='Extract files transferred over TFTP from pcap dumps')

parser.add_argument('filename')

args = parser.parse_args()

if not os.path.exists(args.filename):

raise Exception("File does not exist")

print(f"[+] Loading packets from {args.filename}")

I then declared variables for the current filename, client and server ports, whether write mode was in use, and current file data:

filename = "" # Store filename as a string

filedata = b'' # Store filedata as a set of bytes

# Current server and client transfer ports

server_port = 0

client_port = 0

write_mode = False # Whether write mode is in use

# This changes the data sender from the server to the client.

I then wrote a function to create unique file paths, and another to write the contents of filedata to disk:

# Function to create a unique filename if it already exists.

# Taken from https://stackoverflow.com/questions/13852700/create-file-but-if-name-exists-add-number

def uniquify(path):

if not os.path.exists(path):

return path

filename, extension = os.path.splitext(path)

counter = 1

while os.path.exists(path):

path = filename + "-(" + str(counter) + ")" + extension

counter += 1

return path

# Function to save the file data to disk when done carving a given file out.

def save(filename, filedata):

print(f"[+] Finished transfer of {filename}. Writing to disk...")

unique_filename = uniquify(filename)

writefile = open(unique_filename, "wb")

writefile.write(filedata)

writefile.close()

print(f"[+] Sucessfully carved {filename} as {unique_filename}!")

return "", b''

I then created a loop for scapy’s sniff() function, using a filter for UDP packets.

The sniffed_packet variable is then used throughout the loop to dilter and carve out the data.

for sniffed_packet in sniff(offline=args.filename,filter="udp"):

First, I needed logic to identify the start of a valid connection:

if sniffed_packet[UDP].dport == 69: # Look for connections to the default listiening port: port 69

client_port = sniffed_packet[UDP].sport # Set client port to the source port from the UDP datagram

# If the opcode is 2 ("WRQ" - Write Request), then set the mode accordingly

if sniffed_packet[TFTP].op == 2:

write_mode = True

transfer_type = "write"

else:

write_mode = False

transfer_type = "read"

# Reset the filename and filedata on new transfer

filename = sniffed_packet[TFTP].filename.decode()

filedata = b''

print(f"[+] Found start of new {transfer_type} transfer for file \"{sniffed_packet[TFTP].filename.decode()}\" to {sniffed_packet[IP].dst}:{sniffed_packet[UDP].dport ")

Then, I needed logic for parsing requests sent from the server, parsing TFTP packets, and extracting data if needed:

elif (sniffed_packet[UDP].dport == client_port and client_port != 0):

# Server is sending something to the client over TFTP

# Set server port if it's currently set to the unknown or listening port - this should only happen for the first acknowledgement

if server_port == 69 or server_port == 0:

server_port = sniffed_packet[UDP].sport

if TFTP not in sniffed_packet.layers():

tftp_packet = TFTP(sniffed_packet.load) # Convert raw payload to TFTP if it's not a TFTP packet already

else:

tftp_packet = sniffed_packet[TFTP]

# If we're in write mode, a message from the server should be an acknowledgement.

# If we're in read mode, it should be data that we can add to the filedata variable

if write_mode:

if tftp_packet.op == 5:

# Primitive error handling. I could make this more complex, but it'll work for now.

print(f"[-] Encountered a TFTP error: {tftp_packet[TFTP_ERROR].errormsg.decode()}")

else:

if tftp_packet.op == 3: # opcode for a "DATA" packet is 3

filedata += tftp_packet.load

if len(tftp_packet.load) < 512: # Data blocks should be of length 512 bytes.

# If not, then the transfer has finished, and the file can be written to disk

filename, filedata = save(filename, filedata)

Finally, I needed similar logic for parsing requests sent from the client, parsing TFTP packets, and extracting data if needed:

elif (sniffed_packet[UDP].dport == server_port and server_port != 0):

# Client is sending something to the server over TFTP

if TFTP not in sniffed_packet.layers():

tftp_packet = TFTP(sniffed_packet.load) # Convert raw payload to TFTP if it's not a TFTP packet already

else:

tftp_packet = sniffed_packet[TFTP]

# If we're in write mode, a message from the server should be data.

# If we're in read mode, it should be an acknowledgement

if write_mode:

if tftp_packet.op == 3: # opcode for a "DATA" packet is 3

filedata += tftp_packet.load

if len(tftp_packet.load) < 512: # Data blocks should be of length 512 bytes.

# If not, then the transfer has finished, and the file can be written to disk

filename, filedata = save(filename, filedata)

elif tftp_packet.op == 5:

# Primitive error handling. I could make this more complex, but it'll work for now.

print(f"[-] Encountered a TFTP error: {tftp_packet[TFTP_ERROR].errormsg.decode()}")

And the script was done! I tested it on the first 4 packets of data from tftp.pcapng, and it extracted the contents of the first file, instructions.txt with no problem:

python extractor.py demo.pcapng

[+] Loading packets from demo.pcapng

reading from file demo.pcapng, link-type EN10MB (Ethernet), snapshot length 262144

[+] Found start of new write transfer for file "instructions.txt" to 10.10.10.12:69

[+] Finished transfer of instructions.txt. Writing to disk...

[+] Sucessfully carved instructions.txt as instructions.txt!

[+] Finished carving from file.

Solving the challenge

I ran my script on the tftp.pcapng file, and extracted 6 files:

picture1.bmppicture2.bmppicture3.bmpprogram.debplaninstructions.txt

I started by looking at plan and instructions.txt, which seemed to be encoded text files. Based on the additional characters in both files, I guessed that the encoding was either ROT13 or ROT47. I put both pieces of text into CyberChef with a simple ROT13, and got the following cleartext messages:

TFTPDOESNTENCRYPTOURTRAFFICSOWEMUSTDISGUISEOURFLAGTRANSFER. FIGUREOUTAWAYTOHIDETHEFLAGANDIWILLCHECKBACKFORTHEPLAN

IUSEDTHEPROGRAMANDHIDITWITH-DUEDILIGENCE.CHECKOUTTHEPHOTOS

This revealed that the flags were hidden in the extracted images, and that the transferred program was used to hide the flag.

Attempting to install the program, apt reported that steghide was already installed, so I attempted to use steghide to extract any hidden information.

However, steghide requested a password to extract the information, but the second message said that the message was hid “WITH-DUEDILIGENCE”, which I guessed would be the password. I tried the password “DUEDILIGENCE” on all 3 files, and using the password on picture3.bmp file extracted the flag.

Conclusion

While tools already exist to extract full files from packet captures of TFTP transfers, it’s helpful to know how to develop your own tools to carve data from packet captures, as situations may arise where a novel technique has been used to transfer data covertly over a network. I’d absolutely reccomend taking on a similar challenge for yourself, and avoid using existing tools in a non-competitive environemt.